The rainbow flag means a lot to me – I’m gutted it’s become synonymous with the NHS

By Sandy Downs on Friday 28 January 2022

Until March 2020, most people associated the rainbow flag with LGBTQ pride.

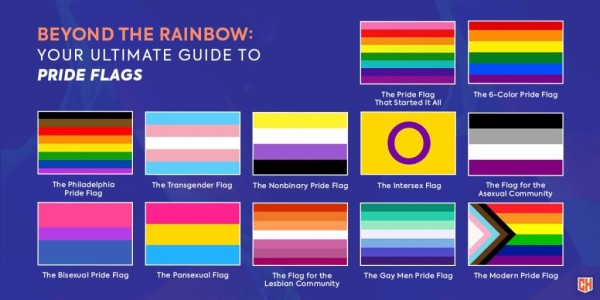

But what many didn’t know is that the rainbow was not just a symbol chosen at random, or adopted by chance… it was designed, carefully and with purpose. In 1978 Gilbert Baker, a gay man and drag queen, designed the first LGBTQ rainbow flag. Harvey Milk had urged him to create a symbol of pride for the community, and Baker believed a flag; a visible, high flying, attention-grabbing flag, fit the bill. He chose 8 colours for the stripes, each with its own meaning - hot pink for sex, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for sunlight, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony, and violet for spirit. Due to production issues, the pink and turquoise stripes were removed, resulting in today’s six stripe flag. The colours are meant to reflect the diversity and unity of the community.

For 14-year-old me, newly out as bisexual and terrified and exhilarated in the middle of Brighton Pride, it meant exactly that. After years of feeling isolated because of my sexuality, there were people everywhere who looked like me. Rainbow jackets, ties, suspenders, glitter, temp tattoos – everywhere you looked, a smorgasbord of colour reminded you that this throng of people was here for one reason… to be part of a community.

As I got to grips with the ways of the world, and the world got to grips (to some extent) with people like me, the meaning evolved a bit. Catching a glimpse of a rainbow meant one of two things – ‘I’m like you’ or ‘I’m here for you’. Allies took to rainbow stash like ducks to water. I knew that if I found myself in hot water but the tube was full of rainbow lanyards, people would have my back. Walking into the doctor’s office, a rainbow flag on a desk meant I wasn’t going to have them respond to my recent sexual history with laughter or cries of ‘what would your mother say’ – both have happened to me when the flags were absent. And rainbow stickers stuck on a backpack meant grins and giggles and awkward flirting – it meant acceptance.

And then the pandemic hit, and we retreated home to our beds, desks, and kitchen tables. Many queer people retreated further, back into the closet. Prides globally were cancelled, and our community was reduced to one of zoom quizzes and TikToks.

Meanwhile, the NHS fought for our lives. They went above and beyond, holding up an underfunded and undervalued institution and doing genuinely incredible work to protect as many of us as they could from the worst of the virus. I will be eternally grateful.

But in the meantime, a symbol was chosen, out of the blue, to say thank you to the NHS. Originally a traditional rainbow – an arc of colours, painted by children and stuck in windows to coincide with the Thursday clap. All happy news.

Yet as these things tend to do, it grew and commercialised. There are now rainbow badges for the NHS, rainbow lanyards for the NHS, rainbow ‘I love my NHS’ tote bags. And the rainbow is not the biblical arc of primary school art class. It’s the 6-stripe rectangle.

Perhaps it wont last forever, but what it does mean is that I’ve lost my confidence. A glimpse of rainbow might mean someone is a lovely person who supports the NHS, but it doesn’t mean they support me. It doesn’t point me to my allies, or to my friends, or potential partners.

To bring this back to the comms world, it is relevant. It’s vital that we’re careful with our brands, with the signs, symbols, and language they co-opt. The brandmark of the rainbow may not be owned by the LGBTQ community (can a community own a brand?) – but it certainly belongs to us.

When we’re choosing branding and logos, getting it wrong risks not only the perception of our brand, but risks the comfort and confidence of our audience. Those in the creative industries must do their research, and have the confidence to push back. Diversity training is critical, and business relevant – without a knowledge of the communities and cultures you’re not part of, you never know what damage you might be doing.