Intertwining Behind the Lens and The Oscar’s Best Picture category

By Sofia Cerchiai on Friday 10 February 2023

It’s fitting for LGBT+ History Month to centre around the theme ‘Behind The Lens’ just as awards season kicks off. Already, The Academy Awards are proving to be a point of contention with the lack of female directors nominated, the absence of Jordan Peele’s Nope, and the fact that Elvis was nominated for best editing (how?). However, the Best Picture category has, in recent years, flourished with LGBT+ cinema being nominated for the coveted award. Previous nominees have included Moonlight in 2016, Call Me By Your Name in 2017, The Favourite in 2018, and The Power of the Dog in 2021.

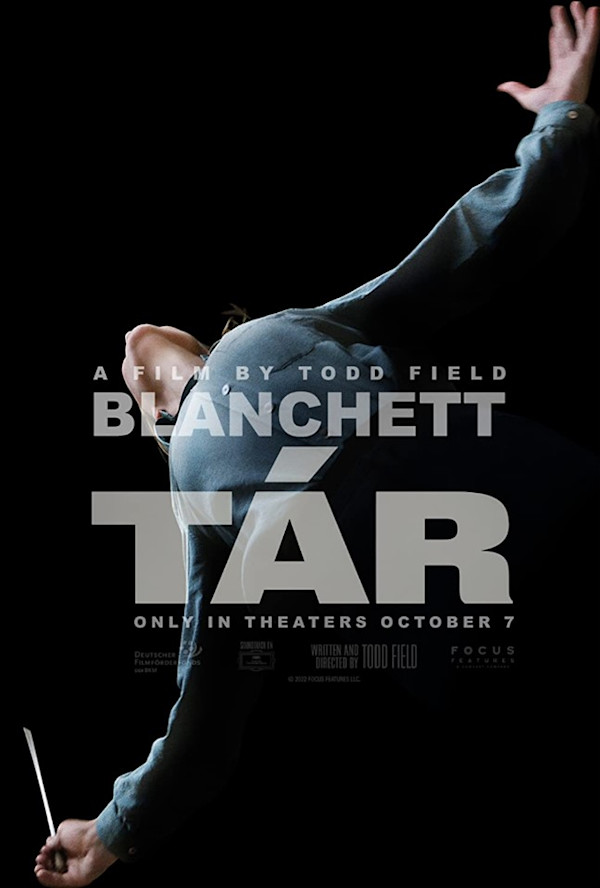

2023 is no exception. Both Everything Everywhere All at Once and Tár have been nominated for Best Picture, and both include lesbian characters in prominent, well written roles which have earned the actresses - Stephanie Hsu and Cate Blanchette - nominations in the acting categories too.

What’s striking here is how different the characters and stories are.

Everything Everywhere All at Once spans across science fiction, comedy, and bittersweet meditations on generational trauma and Chinese diaspora to create an intricate portrait of a mother daughter relationship on the brink. One of the barriers that Joy (Hsu’s character) and Evelyn (her mother, played by Michelle Yeoh) face is Joy’s sexuality, something Evelyn is tolerant of but not entirely supportive of either. Despite Joy’s request for her girlfriend to be introduced as her partner, Evelyn simply refers to her as Joy’s friend, which puts further distance between the two. The extent of her apathy is revealed when she first meets Jobu Tupaki, another version of her daughter, whom she blames her for Joy’s sexuality. Jobu treats with a mix of disbelief and pity, saying “You’re still hung up on the fact that I like girls in this world?” It’s a fair question, especially given that the film ventures across parallel universes and Evelyn is forced to confront bigger issues than her daughter’s queerness or sorting out her taxes.

Perhaps what really helps Evelyn understand the pain Joy feels when her sexuality is dismissed comes when Evelyn finds herself in a universe where she is in a lesbian relationship with Deidre (introduced to us as an IRS inspector, and played by Jamie Lee Curtis). Ignoring the fact that the universe also features everyone having hot dogs for fingers (just go with it), the established relationship between the two illustrates to Evelyn that Joy’s queerness isn’t a phase, but is an inherent part of her. The love Joy holds for her girlfriend isn’t trivial, but is deep and meaningful and deserves to be fully acknowledged and celebrated.

The film may journey to bizarre places with raccoon chefs, martial arts featuring a fanny pack, and nihilistic bagels, but it’s also a story about a mother and daughter connecting and accepting one another, and queerness is an intrinsic part of this.

In complete contrast comes Tár. A psychological drama that examines the fall of fictional composer, Lydia Tár, after she is revealed to be exchanging career advancement with sexual favours from young musicians and conductors. Lydia seems to constantly have to confront ideas of gender and sexuality throughout the film. Her disdain for the gendered term ‘maestra’ is seemingly more contemporary; she says ‘I don't want to self-identify via my sexuality or my gender first and foremost, in the way that men don't necessarily have to within the traditional confines of the classical music world’. We see the way Lydia presents in more masculine aligned clothing, often opting to wear shirts and slacks as an extension of this sentiment. Even when it comes time to pick the cover of a live recording album, she rejects the more suggestive options featuring women for one more classical and male in nature. She refuses to be placed in a box and strives for talent and music to be noticed first, instead of her gender or sexuality.

However, despite shattering the classical music glass ceiling, Lydia also reveals herself to be calculating and manipulative. Her assistant is hinted at being a past lover, however because she’s useful, Lydia passes on her for promotions where she could pursue her career as a conductor, to instead keep her as her assistant. The absent but ever present Krista Taylor, a student-turned-lover-turned-spurned-ex, haunts Lydia’s every step after she torpedoes Krista’s career. When Olga, a young cello player joins the orchestra, Lydia once again follows her pattern of getting close to Olga in the hopes of having an affair. Time and time again, we watch as Lydia repeats her transgressions until finally it catches up with her; a parallel of the #MeToo movement plays out in front of us with a twist on the abuser.

LGBT+ cinema has seen itself originate in queer coded characters and stereotypes, but this year’s Best Picture category is truly a testament to changing times. Yes, there is always work to do to progress the movement and the representation we see on screen, but I would say that we’re seeing a turning point in the kinds of representation we see. We can still expect to see gay characters in films being portrayed as the sassy sidekick or be victims to the ‘bury your gays’ tropes or be paraded as heterosexual even though they’re clearly not (Top Gun: Maverick, I’m looking at you). But we can also have hope for more complex, well written, queer characters. There is still appetite for a variety of stories to be told with gay characters at the forefront, and for it to be recognised by the Academy is a step in the right direction. Personally, I’m excited that we get to see LGBT+ cinema stretch beyond what is expected of it and deliver exceptional film.